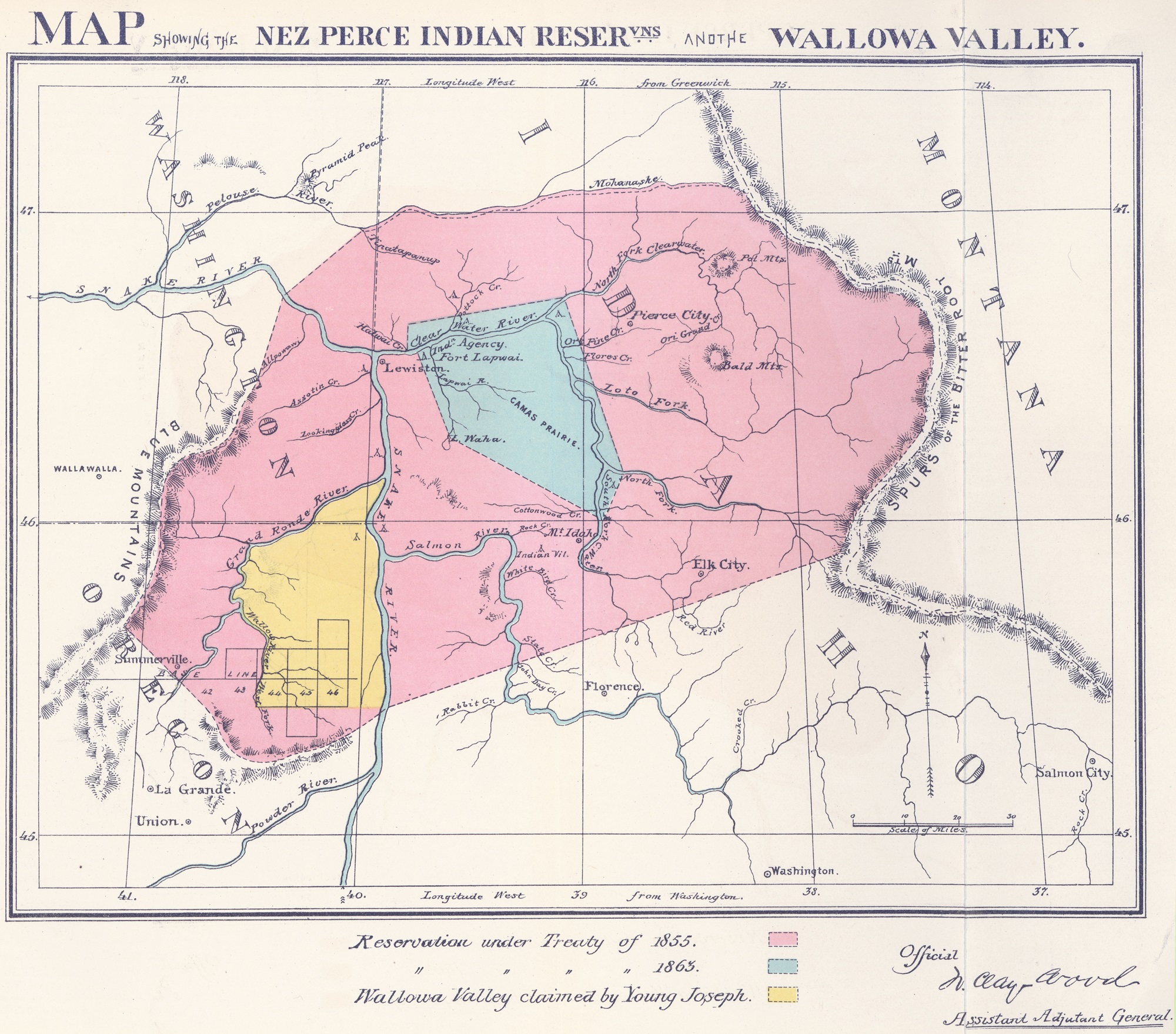

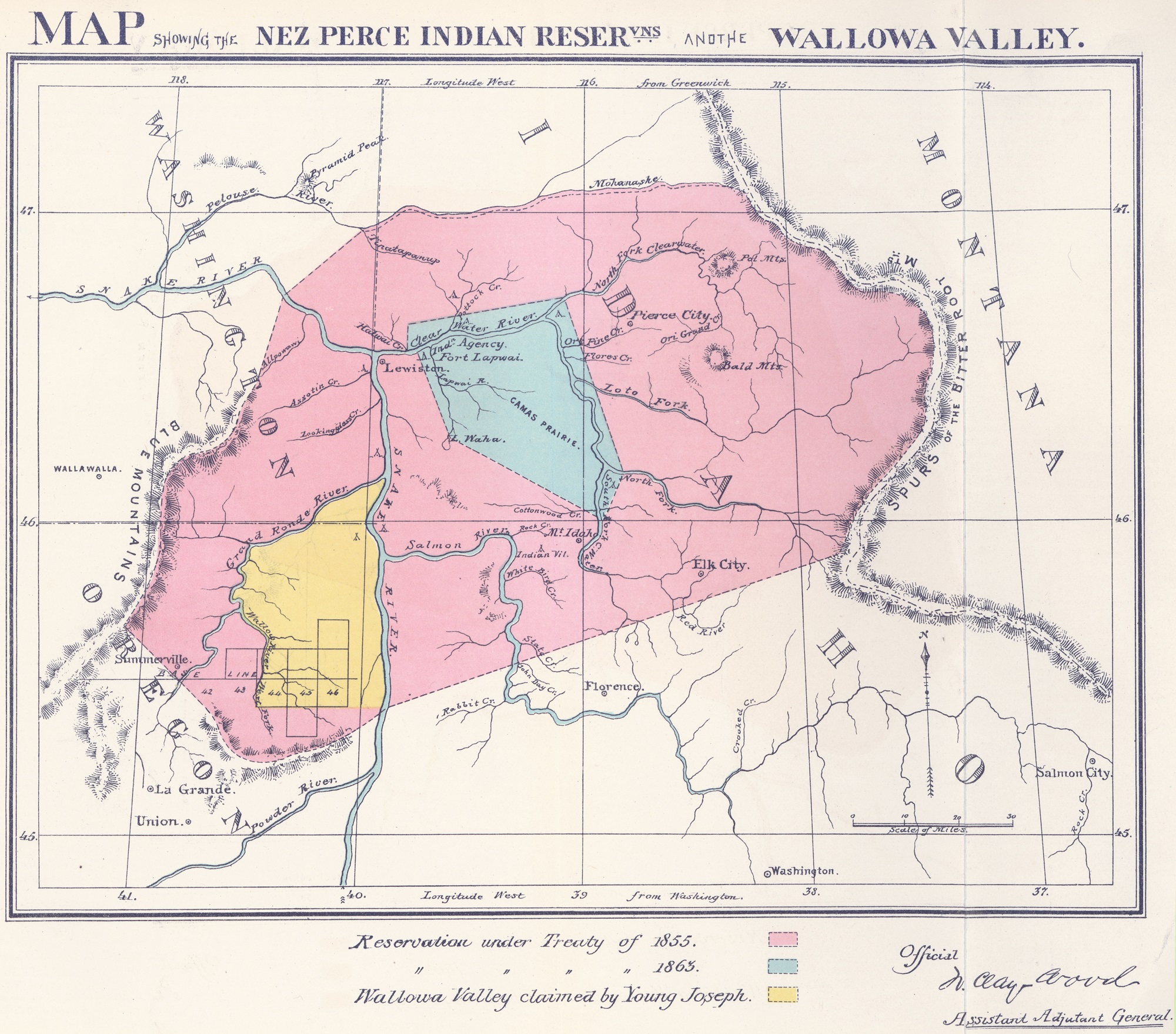

The exhibit explores the Nez Perce Treaties of 1855 and 1863, and a “Proposed Reservation for the Roaming Nez Perce Indians in the Wallowa Valley in Oregon,” promulgated and then rescinded by President U.S. Grant executive orders. The exhibit features historic drawings and paintings, facsimile pages from the treaties, and explanations of treaty language that show their relevance to the present day.

Three tribal artists, Kevin Peters, Phil Cash Cash, and Kellen Trenal, will address the treaties in beads and paint. The art will be on display during the exhibit, and will be available for sale.

This image, courtesy Washington State University Libraries, shows boundary lines of 1855 and 1863 treaties, as well as for President Grant’s proposed “Reservation for the Roaming Nez Perce Indians in the Wallowa Valley in Oregon.” All will be addressed in the exhibit.

Click here to read about our inaugural writer-in-residence for this exhibit, David Liberty.

Virtual Exhibit Preview

1855 PRESENT

Treaties & Reservations

Most people come to the Nez Perce story through the 1200-plus mile fighting retreat that we call the Nez Perce War of 1877. They then work back to the Nez Perce people, their history and culture before the War. That history is enmeshed in two major treaties and an aborted presidential attempt to make things right for one band of Nez Perce, all three of which preceded the Nez Perce War.

1855 PRESENT

Treaties & Reservations

Most people come to the Nez Perce story through the 1200-plus mile fighting retreat that we call the Nez Perce War of 1877. They then work back to the Nez Perce people, their history and culture before the War. That history is enmeshed in two major treaties and an aborted presidential attempt to make things right for one band of Nez Perce, all three of which preceded the Nez Perce War.

1855 Present

Treaties & Reservations

The treaty of 1855, made at Walla Walla, and the Lapwai Treaty of 1863, which shrunk the Nez Perce reservation lands by 90 percent and is often called the “Liars” or “Steal Treaty,” are well documented in the history books. This exhibit is a brief sketch of the people and ideas that addressed treaties and reservation land-promises from 1855-1875, before all collapsed into war in 1877.

1855 Present

Treaties & Reservations

The treaty of 1855, made at Walla Walla, and the Lapwai Treaty of 1863, which shrunk the Nez Perce reservation lands by 90 percent and is often called the “Liars” or “Steal Treaty,” are well documented in the history books. This exhibit is a brief sketch of the people and ideas that addressed treaties and reservation land-promises from 1855-1875, before all collapsed into war in 1877.

1855 Treaty

Treaties & Reservations

In the early June 1855 days of the Walla Walla conference, Isaac Stevens stated his intent to create two reservations: the Spokans, Cayuses, Wallawallas and the Umatillas would move in with the Nez Perce; and several Columbia River bands and tribes would be included on another reservation in the Yakima country.

1855 Treaty

Treaties & Reservations

In the early June 1855 days of the Walla Walla conference, Isaac Stevens stated his intent to create two reservations: the Spokans, Cayuses, Wallawallas and the Umatillas would move in with the Nez Perce; and several Columbia River bands and tribes would be included on another reservation in the Yakima country.

1855 Treaty

Treaties & Reservations

The conclusion of the Walla Walla Treaty Conference, and the treaty-makers’ decision to allow the Nez Perce their own reservation, was influenced by the arrival of Chief Looking Glass from a long trip in the Buffalo Country. The final reservation was not a severe diminishment of lands generally considered Nez Perce, acknowledging their presence and power.

1855 Treaty

Treaties & Reservations

The conclusion of the Walla Walla Treaty Conference, and the treaty-makers’ decision to allow the Nez Perce their own reservation, was influenced by the arrival of Chief Looking Glass from a long trip in the Buffalo Country. The final reservation was not a severe diminishment of lands generally considered Nez Perce, acknowledging their presence and power.

"LIAR'S TREATY" OF 1863

Treaties & Reservations

In 1860 gold was discovered on the Clearwater River on the 1855 Nez Perce Reservation. Within two years over 15,000 white miners were on Indian lands, illegally. In 1863 Superintendent for Indian Affairs in Washington Calvin Hale called a meeting at Lapwai, in which he hoped to reduce Nez Perce lands by almost 90 percent. Chiefs Lawyer and Timothy supported ceding more land; Old Joseph, and White Bird opposed, and refused to sign the new treaty. The two factions, “treaty” and “non-treaty,” agreed to part “friends, but a distinct people.”

"LIAR'S TREATY" OF 1863

Treaties & Reservations

In 1860 gold was discovered on the Clearwater River on the 1855 Nez Perce Reservation. Within two years over 15,000 white miners were on Indian lands, illegally. In 1863 Superintendent for Indian Affairs in Washington Calvin Hale called a meeting at Lapwai, in which he hoped to reduce Nez Perce lands by almost 90 percent. Chiefs Lawyer and Timothy supported ceding more land; Old Joseph, and White Bird opposed, and refused to sign the new treaty. The two factions, “treaty” and “non-treaty,” agreed to part “friends, but a distinct people.”

"LIAR'S TREATY" OF 1863

Treaties & Reservations

Treaty Indians: Superintendent of Indian Affairs Washington and Idaho, Calvin H. Hale, and Nez Perce Chiefs Timothy and Lawyer.

"LIAR'S TREATY" OF 1863

Treaties & Reservations

Treaty Indians: Superintendent of Indian Affairs Washington and Idaho, Calvin H. Hale, and Nez Perce Chiefs Timothy and Lawyer.

"LIAR'S TREATY" OF 1863

Treaties & Reservations

Non-treaty Indians: White Bird, Looking Glass, & Old Joseph. On leaving the council, tiwi·teqis, Old Joseph, tore up his copy of the 1855 treaty and the Nez Perce translation of the Book of Matthew, given to him by missionary Spalding.

"LIAR'S TREATY" OF 1863

Treaties & Reservations

Non-treaty Indians: White Bird, Looking Glass, & Old Joseph. On leaving the council, tiwi·teqis, Old Joseph, tore up his copy of the 1855 treaty and the Nez Perce translation of the Book of Matthew, given to him by missionary Spalding.

Reservation for the Roaming Nez Perce

Treaties & Reservations

President Grant, looking for a way to solve the Indian Problem, moved administration of all Indian reservations to the churches. With the Modoc War in full swing, and formal treaty making stopped by Congress in 1871, Agent Monteith and Superintendent of Indian Affairs Odeneal tried to put Chief Young Joseph and their band on the Umatilla Reservation. When they refused, they were offered half of the Wallowa Country as an “Executive Order Reservation” in 1873. Joseph and Ollokot understood that they would get the east half, which included the Wallowa; the settlers would get the west half. When the order came back from Washington, the division was north-south, with Indians getting the north, and whites the mountains and Wallowa Lake. Although appraisals were made, no money came to purchase settler improvements, and the entire enterprise was rescinded in 1875.

Reservation for the Roaming Nez Perce

Treaties & Reservations

President Grant, looking for a way to solve the Indian Problem, moved administration of all Indian reservations to the churches. With the Modoc War in full swing, and formal treaty making stopped by Congress in 1871, Agent Monteith and Superintendent of Indian Affairs Odeneal tried to put Chief Young Joseph and their band on the Umatilla Reservation. When they refused, they were offered half of the Wallowa Country as an “Executive Order Reservation” in 1873. Joseph and Ollokot understood that they would get the east half, which included the Wallowa; the settlers would get the west half. When the order came back from Washington, the division was north-south, with Indians getting the north, and whites the mountains and Wallowa Lake. Although appraisals were made, no money came to purchase settler improvements, and the entire enterprise was rescinded in 1875.

Nez Perce in the Wallowa Today

Treaties & Reservations

the Nez Perce Tribe works to restore salmon and lamprey in the Wallowa out of a fisheries office in Joseph; the Tribe has owned and managed the 16,268-acre Precious Lands Wildlife Area in the northeast corner of the Wallowa since 1997; the Tribe recently purchased culturally important land on the west moraine of Wallowa Lake. Tribal governments at Lapwai, Umatilla, and Colville all joined to help with the purchase of the Iwetemlaykin State Heritage Site at the foot of Wallowa Lake.

Nez Perce in the Wallowa Today

Treaties & Reservations

the Nez Perce Tribe works to restore salmon and lamprey in the Wallowa out of a fisheries office in Joseph; the Tribe has owned and managed the 16,268-acre Precious Lands Wildlife Area in the northeast corner of the Wallowa since 1997; the Tribe recently purchased culturally important land on the west moraine of Wallowa Lake. Tribal governments at Lapwai, Umatilla, and Colville all joined to help with the purchase of the Iwetemlaykin State Heritage Site at the foot of Wallowa Lake.

Nez Perce in the Wallowa Today

Treaties & Reservations

The Nez Perce Wallowa Homeland brings tribal members from Lapwai, Umatilla, and the Colville Reservation in Washington to an annual powwow—Tamkaliks—on 320 acres at the edge of the town of Wallowa; Indian religious leaders from all three reservations lead services at the new Longhouse on the Homeland grounds; Nez Perce from everywhere sing and dance and host a Friendship Feast at the annual Chief Joseph Days Rodeo; The Nature Conservancy, Wallowa Land Trust and private landowners arrange and host root diggings regularly; and the Wallowa Lake Irrigation District is talking with Indians about restoring the ancient sockeye salmon run.

Nez Perce in the Wallowa Today

Treaties & Reservations

The Nez Perce Wallowa Homeland brings tribal members from Lapwai, Umatilla, and the Colville Reservation in Washington to an annual powwow—Tamkaliks—on 320 acres at the edge of the town of Wallowa; Indian religious leaders from all three reservations lead services at the new Longhouse on the Homeland grounds; Nez Perce from everywhere sing and dance and host a Friendship Feast at the annual Chief Joseph Days Rodeo; The Nature Conservancy, Wallowa Land Trust and private landowners arrange and host root diggings regularly; and the Wallowa Lake Irrigation District is talking with Indians about restoring the ancient sockeye salmon run.

Nez Perce in the Wallowa Today

Treaties & Reservations

3 talented tribal artists: Phil Cash Cash (artwork pictured), Kellen Trenal, and Kevin Peters are all featured in this exhibit. Please come to Josephy anytime through July 26th to view their artwork.

Nez Perce in the Wallowa Today

Treaties & Reservations

3 talented tribal artists: Phil Cash Cash (artwork pictured), Kellen Trenal, and Kevin Peters are all featured in this exhibit. Please come to Josephy anytime through July 26th to view their artwork.